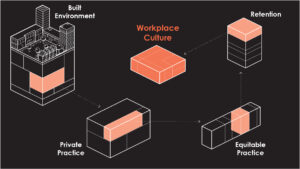

In my final year of the MLA program, I’ve been given the opportunity to participate in the Applied Research Consortium (ARC), a new program within the college that links graduate students, faculty members, and firms to research a topic that aligns student interest, faculty expertise, and firm needs. I am leading a year-long research project focused on racial equity within built environment design practice. More specifically, I am looking at how perceptions of firm culture within private practice affect employee retention. With the help of a few advisors including assistant professor of Landscape Architecture, Catherine De Almeida, I have done a literature review, generated research questions, and scoped out the remaining work. I would like to share some lessons I have learned.

-

- The Built Environment is Racist and so is Design Practice— The built environment is a physical manifestation of our nation’s cultural and political history, and that history is racist. Some well-known examples of racism in the built environment include exclusionary redlining policies and the targeted siting of urban renewal projects, toxic industrial sites and waste sites disproportionately located within communities of color, oppressive architecture of low-income housing projects, and inequitable urban economic development policies.

If our history is racist, and our built environment is racist, then the institutions responsible for designing the built environment must be racist too. This is not a revelatory idea. Racial inequity within built environment design professions is relatively well documented and a regular topic of study, especially in contemporary research. This is partly evidenced by the disproportionately high number of white students in design school and white employees in design practice. The pursuit of anti-racist design practice benefits from an acknowledgement and understanding of existing institutional racism. It is important to align our current reality before we can collectively do better.

- The Built Environment is Racist and so is Design Practice— The built environment is a physical manifestation of our nation’s cultural and political history, and that history is racist. Some well-known examples of racism in the built environment include exclusionary redlining policies and the targeted siting of urban renewal projects, toxic industrial sites and waste sites disproportionately located within communities of color, oppressive architecture of low-income housing projects, and inequitable urban economic development policies.

- Framing Positionality— The identity of the researcher in a project about racial equity is certainly part of the equation. There are inherent power dynamics involved in qualitative research methods like interviews or surveys and the identity of researchers and participants has an impact on the findings and the process. It can be challenging to acknowledge the positionality of the researcher without centering their identity.

I am a cis-gendered, queer, white, man. Appropriately framing my own positionality has come up several times throughout the research process. Some tools I have acquired for navigating issues of positionality include being vulnerable and authentic, acknowledging my mistakes and any potential harm done, remaining open to feedback, practicing deep listening, and working towards a process of reciprocity.

- Layered Barriers to Equity— There are many barriers to a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable design practice. These barriers exist along a spectrum of life experience from early primary education through to retirement. Some examples include the low visibility of design professions in primary and secondary education, the prohibitive cost of post-secondary education, the infamously white culture of academia, skewed hiring practices based on homogenous social networks, unclear promotional criteria, and a further decreased diversity in leadership. This list is non-exhaustive.

Many of these barriers are surface level and cyclical. They create positive feedback loops and perpetuate an ugly cycle. Then there are barriers to inclusive workplaces that are more insidious than a lack of promotional opportunity, for example. A less visible barrier to equity is workplace culture. Every workplace has a unique culture and individuals experience that culture in unique ways. However, one indicator of positive workplace culture is perception alignment. If everyone in an office names and describes the culture in a similar way, that demonstrates a transparent and inclusive culture. A negative workplace culture can be harmful and traumatizing to employees, decrease retention rates, tarnish a reputation, and ultimately be bad for business. Learning how to remove workplace culture from a list of barriers to equity is central to this research.

- Avoid Reification— When conducting social science research with human subjects at a large scale, it is easy to begin treating people like data points. Reducing complex individuals with experiences and emotions to a non-human object is reification and is antithetical to research about equity and justice. A prime example of this is the ‘pipeline,’ a metaphor commonly used to explain how people move through a system. Whether the system is the criminal justice system or career advancement within design practice, the use of the pipeline metaphor reduces individuals to unthinking drops of liquid, incapable of agency. Stripping a human of their humanity, even for the sake of metaphor, is dangerously linked to white supremacy, and is important to acknowledge and avoid.

- Positive Change— Our country’s recent reckoning with anti-Black police violence following the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd lit a proverbial fire under the seats of many white design leaders. Some momentum has been building in the last decade as the design professions slowly began to shift towards more equitable practice.

While some actions spurred on by 2020’s uprisings are dangerously performative; many are earnest. Below is a non-exhaustive list of authors, organizations and networks doing important and positive equity work within the field of design practice.

The next steps of the research are to share a survey collecting experiential information pertaining to workplace culture. I will also be conducting interviews to gather more anecdotal data. Once all the data is collected and analyzed I will create recommendations for how firms can assess and shift their workplaces cultures. I am grateful to be involved in this research and the larger movement to make design practice more inclusive, equitable, and just.

- ACE Mentor Program – A national, free, afterschool program aimed at engaging high school students (69% minority students and 1/3 female students) in the fields of architecture, construction, and engineering.

- Michael Ford + Hip Hop Architecture – “The Hip Hop Architecture Camp® positions Hip Hop culture as a catalyst to introduce underrepresented youth to architecture, urban planning, and design.”

- Dori Tunstall – “Dori Tunstall is the dean of the Faculty of Design at Ontario College of Art and Design University (OCAD University) in Toronto, and the first Black and Black female dean of a faculty of design anywhere in the world.” Dean Tunstall is working to decolonize design education.

- Dark Matter University – A design collective and network with a mission to create new forms of knowledge and knowledge production, new forms of institutions, new forms of practice, new forms of community and culture, and new forms of design.

- Bryan Lee Jr. – Founder and principal at Colloqate, and author of the essay, America’s Cities Were Designed to Oppress, Bryan Lee Jr. provides important commentary on race in the built environment.

- De Nichols + Design as Protest – The DAP Collective, co-organized by De Nichols, Bryan Lee Jr., Taylor Holloway, and Mike Ford, aims to hold the design professions accountable to past harms done to Black communities and a future of anti-racist practice. De Nichols is “an arts-based organizer, social impact designer, serial entrepreneur, and keynote lecturer.” Listen to De on The Nexus, a podcast from the GSD community on intersection between race and design.

- AIA SF Equity by Design Surveys (EQxD) – “Equity by Design was founded to address and minimize barriers in order to maximize our collective potential for success. We have made great strides to collect and disseminate data, while also creating platforms to advance equity, diversity, and inclusion in professions that shape the built environment.”

- Destiny Thomas – Dr. Thomas is an Anthropologist Planner from Oakland, CA, and founder of Thrivance Group. She writes about urbanism and placemaking and its complicity in racism.

- Kofi Boone – His article, Black Landscapes Matter, from UC Berkeley’s Ground Up Journal is a well circulated and culturally significant piece that is accompanied by eight propositions for designers. This is required reading for those who want to learn about anti-racist landscape design practice.

-Jake Minden, MLA Candidate 2021, Landscape Architecture