This story highlights the work of L ARCH 300 Intro to Landscape Architecture Studio in Autumn 2020. It originally appeared in The Daily on November 25, 2019. See the original article.

When UW lecturer Kristi Park assigned her 29 students a project in their landscape architecture class, she had few requirements: use found objects, don’t get arrested, don’t deface public property, don’t get hurt, and be respectful.

When UW lecturer Kristi Park assigned her 29 students a project in their landscape architecture class, she had few requirements: use found objects, don’t get arrested, don’t deface public property, don’t get hurt, and be respectful.

Most of the assignments in L ARCH 300: Introductory Landscape Architecture Design Studio, falls along the lines of typical design projects. But, starting last year, a unique “art activism” project was added to the syllabus. The students were given broad leeway to artistically create something that represents something they are passionate about.

After the projects were turned in, the Community Design Building in West Campus was filled with projects of a huge variety of sizes and mediums, including a couch, a toilet, and a structure covered in vines and foliage.

Park sees landscape architecture as an opportunity to design community spaces that emphasize the core values of equality, accessibility, and environmental responsibility. The idea of activism is a core aspect of the degree program.

While the course provides the necessary design and graphic skills to successfully imagine and implement landscape architectural proposals, a proposal should also emphasize values.

The aesthetic of a visual landscape, like a park, campus, or streetscape, is a high priority in landscape architecture. But Park believes that aesthetics don’t matter if the space is unusable or inaccessible.

“Whether you’re 2 years old, an elder citizen, have accessibility needs, or need to stay in a public space for longer than one might anticipate, I just feel really passionate about designing spaces for everyone,” Park said.

The emphasis on creativity is present throughout L ARCH 300. The studio meets for four-hour class sessions that provide ample opportunity for lively discussions, field trips to the Seattle Parks and Recreation, diverse reading lists, and a variety of projects to practice their design ability.

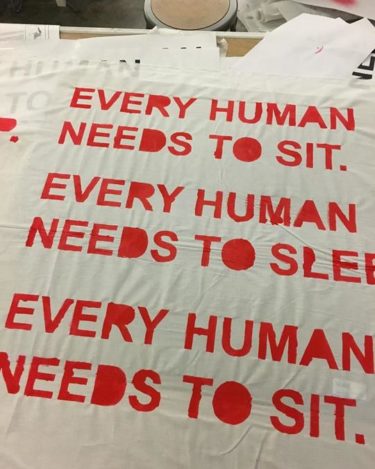

One student, Ava Ross, approached the art activism project by utilizing a couch to highlight the use of hostile architecture in Seattle. Her “Luxury Couch” had large prints on it that read “Every human needs to sleep. Every human needs to sit.”

“If you can’t have a private space because you’re experiencing homelessness, but you can’t exist in these public spaces and have these basic human needs met, like sitting and sleeping, then where are you supposed to go?” Ross said.

She noted that urban areas, including Seattle, take efforts to make seating in public spaces unusable by putting spikes on a ledge or placing a bar on a bench so people can’t lay down. By doing this, people experiencing homelessness are pushed to the edges of society.

“The art activism project has allowed students to see the design sequence in totality and also helps them to begin to develop a point of view,” Park said.

The couch was rolled to various places around campus and the U-District, prompting onlookers to recognize that a couch is considered a necessity by those with homes, but is often seen as a luxury for those with limited access to indoor spaces. Ross explained that it was meant to blur the lines between public and private spaces.

“It was interesting to see people interact with it, because people were taking photos of it,” Ross said. “The coolest part was there was actually a family sitting on it.”

In addition to teaching, Park is a professional landscape architect. In her work, she has practiced what she preaches. One recent project she worked on was the open parks and planning process with the Stillaguamish Tribe in Arlington.

“Getting to work with the Stillaguamish community was definitely an honor of my lifetime,” Park said. “Just to weave cultural stories and ethnobotany and community involvement into the landscape in the projects we were building was a really awesome experience.”

Throughout the process, Park engaged with Stillaguamish youth, having them participate in nature-based art projects of their own and give feedback on some of the design ideas.

Having not discovered landscape architecture until her thirties, Park sees working with communities, like the Stillaguamish, as a way to enhance the visibility of landscape architecture and the opportunities for creativity and community involvement it provides as a potential career.