This month we are spotlighting Steve Moddemeyer (BLA 1989). Steve works in Seattle and is a principal with CollinsWoerman, an architecture and planning firm. His work focuses on creative planning and policy strategies that promote urban resilience and sustainability.

UWLA: Could you outline your professional journey between graduation and today?

S: My first job was working as an urban designer at a small start-up firm. I worked there for two years until the partners parted ways over the Christmas holidays. Fortunately, I was at a Christmas party and a friend let me know about an environmental planning job with a Tribe on the Olympic Peninsula. I ended up working for the Tribe for almost three years. My work focused on issues related to natural resource management, and mitigating the impacts of development on habitat. I represented the Tribe with land use negotiations, and it was an incredible opportunity to learn about and interact with every level of government. The Tribe was an incredible source of knowledge about the tensions that exist in the interactions between government assistance and cultural, land use, and environmental systems. During this time, I also had the opportunity to represent the Tribe while working on one of the first watershed plans in the state of Washington.

After about three years, I moved to the City of Seattle Water Department to help establish Central Puget Sound watershed planning efforts. Over time I started focusing more on the interaction between urban form and habitat. When several species of salmon were listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act, I helped launch the city’s “Salmon Friendly Seattle.” At the time, most folks didn’t want to pollute water but didn’t see protecting habitat as their responsibility, so we started thinking about how government and homeowners make choices to protect habitat in urban areas. I also worked on many issues including integrated water strategies and intergovernmental relations. During my last two years with the city, I transferred to the planning department to incorporate sustainability thinking into land use policy and government spending.

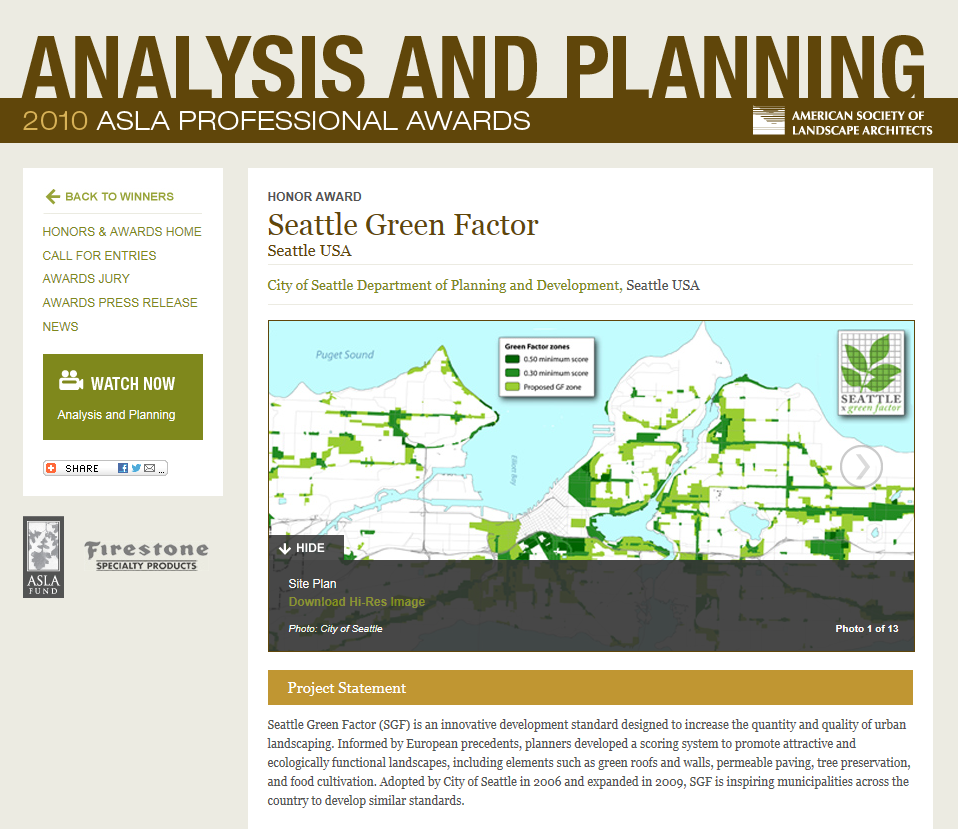

Steve led the development of the award-winding Seattle Green Factor: https://www.asla.org/2010awards/519.html

Steve led the development of the award-winding Seattle Green Factor: https://www.asla.org/2010awards/519.html

By then it had been about 14 years since my first job, and I always assumed I would make the shift back to consulting. When CollinsWoerman offered me a job, I basically said, “I want to work with cities and utilities on advanced sustainability thinking. Would you support me in developing a practice doing that, and I’ll support you in making your practice more sustainable?” We agreed, and I just celebrated my nine-year anniversary here.

UWLA: Your journey took you in quite a few directions! How did your time at UW inform some of these movements out of design?

S: I actually didn’t go to college for 10 years after I graduated high school. During those years, I was a carpenter, an artist, and a musician. By the time I got to the University of Washington, I was already my own person and the things that interested me involved nature, art, and creativity. I thought of going back to school as analogous to learning my scales—if you play jazz, you can doodle and play fun stuff, but if you know what lies underneath you can achieve more mastery. In a way, I built the foundation after I already had the music.

Another fantastic aspect of the UW was the depth of the library and the depth of the expertise. For example, I took a dance class; in learning Laban movement analysis I gained a lot of understanding that is still valuable to me today. I felt that if I was willing to keep showing up, there was no end to what I could learn.

Along Brooklyn Ave in the UDistrict. (photo credit: KUOW) Check out the KUOW Story: http://kuow.org/post/when-seattles-big-storm-hits-let-streets-become-rivers

Along Brooklyn Ave in the UDistrict. (photo credit: KUOW) Check out the KUOW Story: http://kuow.org/post/when-seattles-big-storm-hits-let-streets-become-rivers

UWLA: Can you speak to a pivotal moment in your education?

S: I was taking a wetlands design course from Sally Schauman, who was Department Chair at the time. When she assigned our first project, I asked her if she wanted me to just use what we had been taught, or to apply other things that I knew. She replied, “I want you to apply everything you know.” It was like I was suddenly encouraged to bring all of me into every part of what I was doing. To me that was just perfect—I’ve used her permission in all of my careers.

That is the freedom that landscape architecture has as a discipline and profession; it’s this wonderful mix of humans, nature, cultivated nature, technique, and the ability to weave it all into a culturally informed, artistic whole. In working with clients, translation and the cross-application of concepts has always been important to me.

UWLA: How does creativity still manifest in your career, given that design is a very explicitly creative aspect of what we do, but consultation requires other skills like flexible thinking?

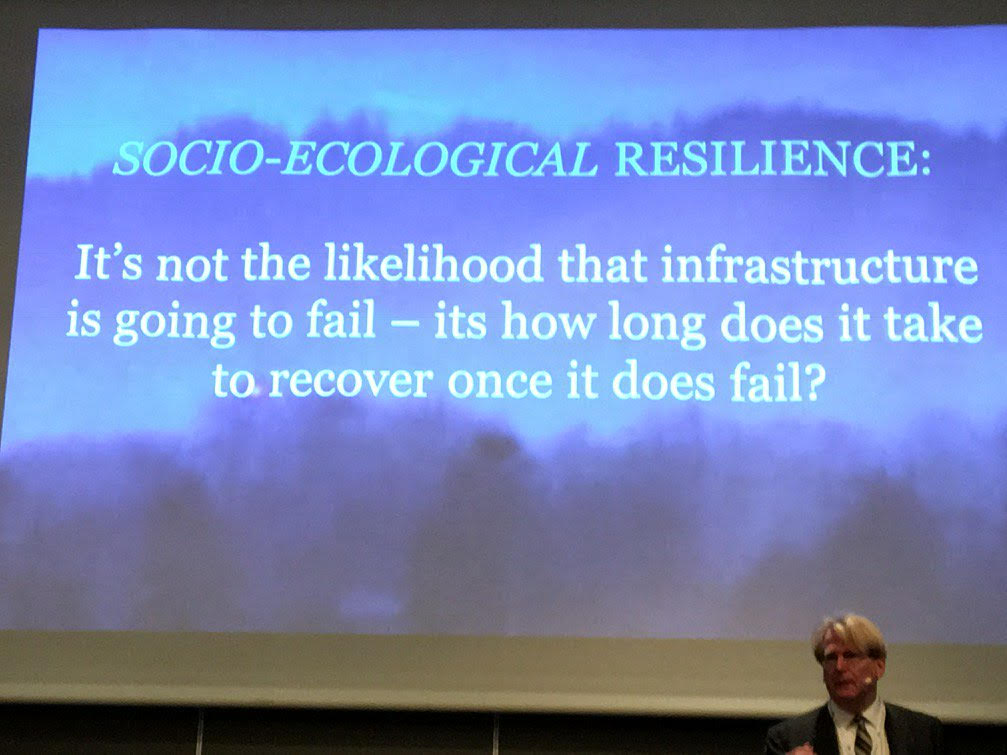

S: The difference between creativity and innovation is key. Since I’m kind of a urban planner now, I’ve been exploring the concepts that frame socio-ecological resilience, asking myself how our understanding of natural system functions could be applied to our thinking about cities and their operations. I’m not creating anything new necessarily, but I’m being innovative in the sense of extracting, reconfiguring, and determining strategies for implementation. It’s a little bit like biomimicry, but what’s different is that socio-ecological resilience looks at how species adapt to changes while maintaining their individual identity.

What is it about humans that makes them resilient, and how can we apply what we know to build and manage our infrastructural systems? That’s where I’m being creative; I’m writing about “How do you do this?”, “What does it mean?”, and “What is the practical application?”

On a different note, I play the tuba and write music for a brass quartet. So in the most traditional sense, that is probably my most creative outlet. When engaged in writing music, it’s like sensory deprivation; everything else goes away. You go into this place that you’re creating and because it’s music, it’s emotion, and there’s a form and language to it.

UWLA: Given you have been in the field for quite a while, how has your relationship with the discipline evolved?

S: When I was going to the UW there was an emphasis on aesthetics; most people were studying the art of landscape architecture. I really liked that perspective, but was also happy when we began to integrate technology and knowledge of the ecological and physical sciences that underpin it all. Aesthetics are important as is a deep understanding of landscape processes and human dynamics.

Landscape architecture is a fantastic field with an extremely powerful essence, but I would like it to be rebranded. I stopped telling people I studied landscape architecture because they would just jump to the conclusion that I was going to redesign their backyard. I would say if there was a marketing challenge that would be it. How do we reframe the profession to the larger public? How do we get people to understand that landscape architecture has the right tools that can help our world to understand and manage the dynamics between nature and society?

UWLA: Our last question is somewhat in line with that, but more spatial and localized within Seattle. Given how rapidly it’s developing and changing, how has your work gone along with that process or have you had to adapt to it?

S: My first thought has to do with how we’re building all these high-rise buildings where too many will be teardowns after the next big earthquake. We just built a new generation of buildings in South Lake Union to a minimum life-safety standard to withstand earthquake shaking. Life safety is good as more people will survive. But if the building itself is unusable, think of all the months and years it will take us to recover. We shouldn’t externalize the recovery to the survivors. Yet that’s what we do when we do not include recovery in our design.

Experience shows us that the longer the recovery the greater the suffering for surviving individuals, families, and local businesses. We should be thinking seriously about building to a higher habitability standard instead of this minimum.

Presenting at a conference in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Presenting at a conference in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Socio-ecological resilience thinks about designing cities and human habitat with as much resilience as salmon habitat. This is completely doable and doesn’t necessarily require new technology, just a different perspective on how we develop and manage our city. The key difference is that we currently design systems to resist —a storm of a certain size, or an earthquake of a certain size—we just resist change up to a certain level, which is great when the things that knock us back are rare. But with climate change, meteorological change, and earthquakes, things that are only designed to resist are going to be breaking down more often. We ought to be redesigning our systems to recover quickly and to respond adaptively and flexibly when change does happen.

Ultimately, how our city changes and emerges over time needs to incorporate insights from the way nature adapts to change. As landscape architects who are already working at the intersection between natural and built systems, we have the skills and capacity to do that, if we choose.