The following article was written by MLA student Lauren Iversen for The Field, the ASLA Professional Practice Networks’ Blog.

Under my wide brimmed hat, with sweat dripping, I added paint, stroke by stroke, to the long wall. My legs burned sitting on the decomposed granite roasting in the hot sun. I sipped Cool Blue Frost Gatorade, hunger dissipated by 110° heat. A giant cottonwood shaded the playground in the afternoon, but at midday there was nowhere to hide. I looked behind me. Pavers in bright pink and green lay scattered about. Soon I would have to muster the energy to dig up the remaining pavers, wincing at the first attempt to lay a labyrinth. Next to the pavers, the newly planted Desert King fig reflected bright green fruit, leaves wilted trying to send all its efforts in the heat to its future. “Will these figs be around when the kids come back for school?” “Will I ever finish painting this wall?” Why did I get myself into this mess?”

In the 2017-2018 school year I found myself leading efforts to reimagine a field that had succumbed to sand from the desert heat. Working as a second-grade teacher with a BLA, a culmination of timing and tenacity led to a moment that morphed into an actual plan to build the playground. With my background, I embodied the role of designer, fundraiser, project manager, and community advocate. So, how do you build a playground without any money? In the end, the WHY was more important than HOW; therefore, it got done.

Why?

1. In 2017, Nevada schools ranked at 51st for best schools in the nation—as in, the absolute worst. Something had to be done, all options on the table. At my school, over 90% of children received free and reduced lunches. A minority community, parents worked demanding jobs in the thriving entertainment industries to provide for their children. The city provided little in return. From 2016 to 2018, the Clark County School District had a $60 million funding deficit [i, ii]. In 2017 the district spent $4,096 less per student than the national average [iii]. Our school was focused on improving education, trying its best to not lose teachers and resources due to the budget deficit. Clearly, no money was available for playground infrastructure.

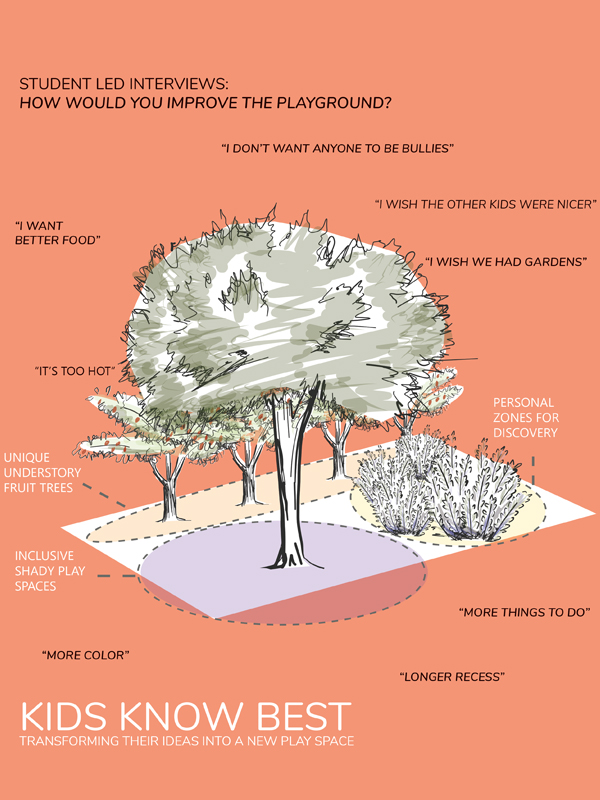

2. Urban environments such as our school neighborhood are stressful for children. Children often have limited zones for exploration and discovery, with little or no access to nature. During my time at the school, students had no walking access to nearby parks. Many had never visited the plentiful wilderness around Las Vegas, like the Red Rock Canyon Conservation Area just 15 miles west.

3. I asked myself which came first: the unruly child or limited recess? With increasing pressure for under-performing schools to improve, administrators are forced to limit recess to focus on core subjects. At my school, teachers became frustrated by students playing in the bathroom, their inattention, and extreme energy in the classroom. Children need unstructured play time between academics, for both physical and mental health. Could a better play environment make up for these challenges? I couldn’t say for sure, but perhaps it could maximize play time, provide outdoor classroom space, and increase nature views from the classroom window. Ideally, it would reduce student stress and disruptive behaviors.

How?

1. A community project needs relationships and money. Fundraising came through a Youth Neighborhood Association Partnership Program (YNAPP) grant, finding community partners, and utilizing the supportive internal school community. My Principal’s support and trust in the project was critical, and my Teach for America colleagues supported efforts by helping build the project and connect me to community partners. These key relationships meant finding enough money and resources to complete the project.

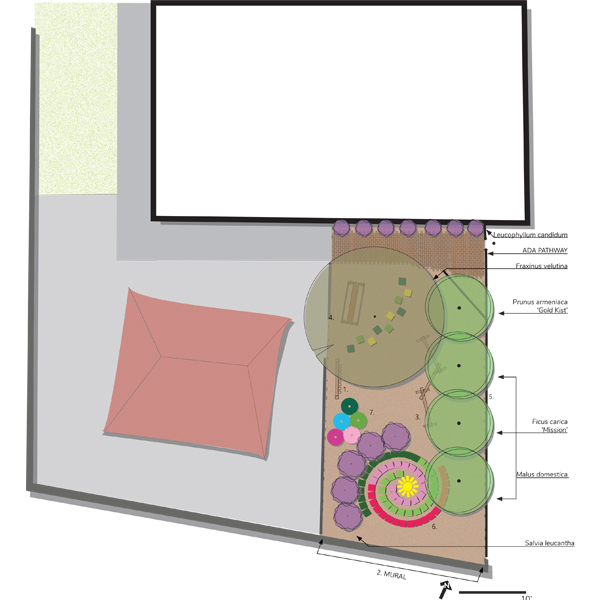

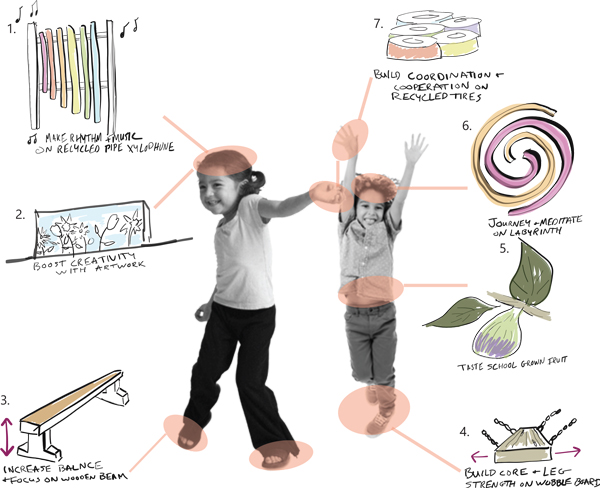

My background in landscape architecture provided tools to create plans and design. Using playground design principles intended to improve students’ physical and mental health was a goal. Varied types of balance beams were cheap and easy to build. A labyrinth could be a beautiful discovery, surrounded by native plants and a colorful mural. Incorporating sensory elements like a large xylophone and fruit trees stimulate and appeal to children.

3. Commitment. At some point during grant funding interviews, I realized that I was committed to this project. The students who were involved were dependent on me to help make their goals come to life. I realized my decisions would make or break the project, a responsibility I felt immensely. However stressful, the students were committed and excited, as was I to meet their expectations.

I left the school at the end of the summer to pursue an MLA, knowing there are other needed outdoor projects I could not initiate. There was a group of children I knew I would never see again, those who made me laugh until my sides hurt, and I miss them. I hope that what I left was a catalyst for change. There is movement in Las Vegas for more positive outdoor environments by many hard-working groups and individuals. This playground project taught me about advocating for natural spaces and play space for children. It taught me to be intuitive, innovative, resourceful, and community-oriented. What I accomplished is not ground-breaking, it was about making a positive change. It is not easy to change large institutions. It requires boldness and confidence in the face of adversity, grassroots passion, and smiling kids. I hope others will be motivated by the efforts of these students to continue the path towards environmental equality for all children.

[i] Pak-Harvey, Amelia. “$60M Impact of Tax Breaks on Nevada Schools Stirs Debate.” Las Vegas Review-Journal, Las Vegas Review-Journal, 11 Dec. 2018.

[ii] Pak-Harvey, Amelia. “Clark County Schools Cut More than 550 Jobs to Erase Deficit.” Las Vegas Review-Journal, Las Vegas Review-Journal, 22 June 2018.

[iii] Turner, Cory, et al. “Why America’s Schools Have A Money Problem.” NPR, NPR, 18 Apr. 2016.

Lauren Iversen is a Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) student at the University of Washington.

This article was written by Lauren Iversen. It originally appeared in The Field, the ASLA Professional Practice Networks’ Blog on April 4, 2019. For the original article, visit https://thefield.asla.org/2019/04/04/gambling-on-green-a-playground-renovation-in-las-vegas-nevada/.